Ancient Roman Fashion Male Vs Female

Statue of the Emperor Tiberius showing the draped toga of the 1st century Ad

Clothing in ancient Rome mostly comprised a short-sleeved or sleeveless, knee-length tunic for men and boys, and a longer, usually sleeved tunic for women and girls. On formal occasions, adult male citizens could wearable a woolen toga, draped over their tunic, and married citizen women wore a woolen pall, known every bit a palla, over a stola, a elementary, long-sleeved, voluminous garment that hung to midstep. Clothing, footwear and accoutrements identified gender, status, rank and social class. This was especially apparent in the distinctive, privileged official dress of magistrates, priesthoods and the armed services.

The toga was considered Rome's "national costume," simply for twenty-four hour period-to-day activities most Romans preferred more casual, practical and comfortable article of clothing; the tunic, in various forms, was the basic garment for all classes, both sexes and almost occupations. It was usually made of linen, and was augmented as necessary with underwear, or with diverse kinds of cold-or-moisture weather condition wear, such equally knee-breeches for men, and cloaks, coats and hats. In colder parts of the empire, full length trousers were worn. Most urban Romans wore shoes, slippers, boots or sandals of various types; in the countryside, some wore clogs.

Well-nigh clothing was elementary in structure and basic form, and its product required minimal cut and tailoring, merely all was produced by mitt and every process required skill, cognition and time. Spinning and weaving were thought virtuous, frugal occupations for Roman women of all classes. Wealthy matrons, including Augustus' wife Livia, might show their traditionalist values by producing domicile-spun clothing, but most men and women who could beget it bought their clothing from specialist artisans. The industry and trade of clothing and the supply of its raw materials made an of import contribution to Rome's economy. Relative to the overall bones price of living, fifty-fifty simple wearable was expensive, and was recycled many times down the social scale.

Rome's governing elite produced laws designed to limit public displays of personal wealth and luxury. None were specially successful, as the same wealthy elite had an appetite for luxurious and fashionable clothing. Exotic fabrics were bachelor, at a price; silk damasks, translucent gauzes, cloth of aureate, and intricate embroideries; and vivid, expensive dyes such equally saffron yellowish or Tyrian majestic. Not all dyes were costly, still, and most Romans wore colourful wear. Make clean, brilliant article of clothing was a mark of respectability and condition among all social classes. The fastenings and brooches used to secure garments such equally cloaks provided farther opportunities for personal embellishment and display.

Tunics and undergarments

The basic garment for both genders and all classes was the tunica (tunic). In its simplest form, the tunic was a single rectangle of woven fabric, originally woolen, merely from the mid-democracy onward, increasingly fabricated from linen. It was sewn into a wide, sleeveless tubular shape and pinned effectually the shoulders like a Greek chiton, to form openings for the cervix and arms. In some examples from the eastern part of the empire, neck openings were created in the weaving. Sleeves could be added, or formed in situ from the excess width. Virtually working men wore knee-length, short-sleeved tunics, secured at the waist with a belt. Some traditionalists considered long sleeved tunics advisable but for women, very long tunics on men equally a sign of effeminacy, and short or unbelted tunics every bit marks of servility; nonetheless, very long-sleeved, loosely belted tunics were also fashionably unconventional and were adopted by some Roman men; for case, by Julius Caesar. Women's tunics were unremarkably talocrural joint or foot-length, long-sleeved, and could be worn loosely or belted.[1] For condolement and protection from cold, both sexes could vesture a soft under-tunic or vest (subucula) beneath a coarser over-tunic; in winter, the Emperor Augustus, whose physique and constitution were never especially robust, wore up to four tunics, over a vest.[2] Although essentially simple in basic pattern, tunics could also be luxurious in their fabric, colours and detailing.[iii]

Loincloths, known as subligacula or subligaria could be worn under a tunic. They could as well exist worn on their own, particularly by slaves who engaged in hot, sweaty or muddy work. Women wore both loincloth and strophium (a breast material) under their tunics; and some wore tailored underwear for work or leisure.[4] A 4th-century Advertizing Sicillian mosaic shows several "bikini girls" performing able-bodied feats; in 1953 a Roman leather bikini bottom was excavated from a well in London.

Formal wear for citizens

Roman society was graded into several denizen and non-citizen classes and ranks, ruled by a powerful minority of wealthy, landowning citizen-aristocrats. Even the lowest grade of citizenship carried certain privileges denied to non-citizens, such every bit the right to vote for representation in government. In tradition and law, an individual'southward place in the citizen-hierarchy – or exterior information technology – should be immediately evident in their clothing. The seating arrangements at theatres and games enforced this idealised social lodge, with varying degrees of success.

In literature and verse, Romans were the gens togata ("togate race"), descended from a tough, virile, intrinsically noble peasantry of difficult-working, toga-wearing men and women. The toga's origins are uncertain; information technology may have begun as a simple, practical piece of work-garment and blanket for peasants and herdsmen. It eventually became formal wearable for male citizens; at much the same time, respectable female citizens adopted the stola. The morals, wealth and reputation of citizens were discipline to official scrutiny. Male person citizens who failed to meet a minimum standard could be demoted in rank, and denied the right to wear a toga; past the same token, female citizens could be denied the stola. Respectable citizens of either sex might thus be distinguished from freedmen, foreigners, slaves and infamous persons.[half-dozen]

Toga

The toga virilis ("toga of manhood") was a semi-elliptical, white woolen cloth some six anxiety in width and 12 feet in length, draped across the shoulders and around the trunk. It was usually worn over a evidently white linen tunic. A commoner'south toga virilis was a natural off-white; the senatorial version was more voluminous, and brighter. The toga praetexta of curule magistrates and some priesthoods added a broad majestic edging, and was worn over a tunic with two vertical purple stripes. Information technology could too be worn by noble and freeborn boys and girls, and represented their protection under civil and divine law. Equites wore the trabea (a shorter, "equestrian" form of white toga or a purple-cherry wrap, or both) over a white tunic with two narrow vertical royal-red stripes. The toga pulla, used for mourning, was made of dark wool. The rare, prestigious toga picta and tunica palmata were royal, embroidered with gold. They were originally awarded to Roman generals for the twenty-four hour period of their triumph, simply became official clothes for emperors and Imperial consuls.

From at least the late Republic onward, the upper classes favoured always longer and larger togas, increasingly unsuited to manual piece of work or physically agile leisure. Togas were expensive, heavy, hot and sweaty, hard to keep clean, costly to launder and challenging to wear correctly. They were best suited to stately processions, oratory, sitting in the theatre or circus, and self-display among peers and inferiors while "ostentatiously doing nothing" at salutationes.[7] These early on morning, formal "greeting sessions" were an essential role of Roman life, in which clients visited their patrons, competing for favours or investment in business organisation ventures. A client who dressed well and correctly – in his toga, if a citizen – showed respect for himself and his patron, and might stand out among the crowd. A canny patron might equip his entire family, his friends, freedmen, even his slaves, with elegant, costly and impractical clothing, implying his unabridged extended family's condition as one of "honorific leisure" (otium), buoyed by limitless wealth.[8]

The vast majority of citizens had to work for a living, and avoided wearing the toga whenever possible.[nine] [ten] Several emperors tried to compel its employ as the public dress of true Romanitas only none were particularly successful.[eleven] The aristocracy clung to it equally a marking of their prestige, just somewhen abandoned information technology for the more comfortable and practical pallium.

Stola and palla

Roman marble torso from the 1st century AD, showing a woman'southward clothing

Likewise tunics, married citizen women wore a simple garment known as a stola (pl. stolae) which was associated with traditional Roman female virtues, especially modesty.[12] In the early Roman Republic, the stola was reserved for patrician women. Soon earlier the 2nd Punic War, the right to wear it was extended to plebeian matrons, and to freedwomen who had caused the condition of matron through marriage to a citizen. Stolae typically comprised 2 rectangular segments of cloth joined at the side by fibulae and buttons in a style allowing the garment to be draped in elegant but concealing folds.[xiii]

Over the stola, citizen-women ofttimes wore the palla, a sort of rectangular shawl upward to xi feet long, and 5 broad. It could be worn as a glaze, or draped over the left shoulder, under the right arm, then over the left arm. Outdoors and in public, a chaste matron'southward pilus was bound up in woolen bands (fillets, or vitae) in a loftier-piled style known as tutulus. Her face was curtained from the public, male gaze with a veil; her palla could as well serve as a hooded cloak.[14] [fifteen] Two ancient literary sources mention utilize of a coloured strip or edging (a limbus) on a woman's "mantle", or on the hem of their tunic; probably a mark of their high status, and presumably imperial.[16] Outside the confines of their homes, matrons were expected to article of clothing veils; a matron who appeared without a veil was held to take repudiated her wedlock.[17] High-degree women convicted of adultery, and loftier-class female prostitutes (meretrices), were not only forbidden public use of the stola, but might have been expected to wear a toga muliebris (a "adult female'southward toga") equally a sign of their infamy.[xviii] [19]

Freedmen, freedwomen and slaves

For citizens, salutationes meant wearing the toga appropriate to their rank.[20] For freedmen, information technology meant whatever clothes disclosed their condition and wealth; a man should exist what he seemed, and low rank was no bar to making coin. Freedmen were forbidden to wear any kind of toga. Elite invective mocked the aspirations of wealthy, upwards mobile freedmen who boldly flouted this prohibition, donned a toga, or even the trabea of an equites, and inserted themselves every bit equals among their social superiors at the games and theatres. If detected, they were evicted from their seats.[21]

Nevertheless the commonplace snobbery and mockery of their social superiors, some freedmen and freedwomen were highly cultured, and most would have had useful personal and business connections through their former master. Those with an bent for business could amass a fortune; and many did. They could office every bit patrons in their ain right, fund public and private projects, ain one thousand town-houses, and "dress to impress".[22] [23]

There was no standard costume for slaves; they might dress well, badly, or barely at all, depending on circumstance and the volition of their owner. Urban slaves in prosperous households might vesture some form of livery; cultured slaves who served as household tutors might exist indistinguishable from well-off freedmen. Slaves serving out in the mines might article of clothing nil. For Appian, a slave dressed as well as his master signalled the stop of a stable, well-ordered gild. According to Seneca, tutor to Nero, a proposal that all slaves be fabricated to wear a particular type of habiliment was abased, for fear that the slaves should realise both their ain overwhelming numbers, and the vulnerability of their masters. Advice to farm-owners by Cato the Elder and Columella on the regular supply of adequate clothing to farm-slaves was probably intended to mollify their otherwise harsh conditions, and maintain their obedience.[24] [25] [26]

Children and adolescents

Roman infants were ordinarily swaddled. Apart from those few, typically formal garments reserved for adults, most children wore a scaled-downward version of what their parents wore. Girls often wore a long tunic that reached the foot or instep, belted at the waist and very simply decorated, most often white. Outdoors, they might vesture another tunic over it. Boys' tunics were shorter.

Boys and girls wore amulets to protect them from immoral or baleful influences such as the evil heart and sexual predation. For boys, the amulet was a bulla, worn around the neck; the equivalent for girls seems to have been a crescent-shaped lunula, though this makes merely rare appearances in Roman art. The toga praetexta, which was idea to offering similar apotropaic protection, was formal vesture for freeborn boys until puberty, when they gave their toga praetexta and childhood bulla into the intendance of their family lares and put on the adult male's toga virilis. According to some Roman literary sources, freeborn girls might also vesture – or at least, had the right to clothing – a toga praetexta until marriage, when they offered their childhood toys, and perhaps their maidenly praetexta to Fortuna Virginalis; others claim a gift made to the family Lares, or to Venus, as part of their passage to adulthood. In traditionalist families, unmarried girls might be expected to clothing their hair demurely bound in a fillet.[27] [28]

Yet such attempts to protect the maidenly virtue of Roman girls, there is petty anecdotal or artistic evidence of their employ or constructive imposition. Some unmarried daughters of respectable families seem to take enjoyed going out and about in flashy article of clothing, jewellery, perfume and brand-upward;[29] and some parents, broken-hearted to discover the all-time and wealthiest possible match for their daughters, seem to have encouraged it.[30]

Footwear

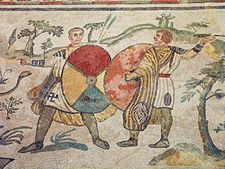

Left paradigm: The goddess Diana hunting in the woods with a bow, and wearing the high-laced open "Hellenistic shoe-boots" associated with deities, and some images of very high status Romans. From a fresco in the Via Livenza Hypogeum, Rome, c. 350 Advertizing

Right epitome: Detail of the "Big Game Hunt" mosaic from the Villa Romana del Casale (fourth century Ad), Roman Sicily, showing hunters shod in calceii, wearing vari-coloured tunics and protective leggings

Romans used a wide variety of practical and decorative footwear, all of it flat soled (without heels). Outdoor shoes were often hobnailed for grip and durability.[31] The most common types of footwear were a one-slice shoe (carbatina), sometimes with semi-openwork uppers; a usually sparse-soled sandal (solea), secured with thongs; a laced, soft half-shoe (soccus); a usually hobnailed, thick-soled walking shoe (calcea); and a heavy-duty, hobnailed standard-result military marching boot (caliga). Thick-soled wooden clogs, with leather uppers, were available for employ in wet conditions, and by rustics and field-slaves[32]

Archaeology has revealed many more unstandardised footwear patterns and variants in employ over the being of the Roman Empire. For the wealthy, shoemakers employed sophisticated strapwork, delicate cut, dyes and even gold leaf to create intricate decorative patterns. Indoors, about reasonably well-off Romans of both sexes wore slippers or light shoes of felt or leather.[32] Brides on their hymeneals-day may have worn distinctively orangish-coloured lite soft shoes or slippers (lutei socci).[33]

Public protocol required red ankle boots for senators, and shoes with crescent-shaped buckles for equites, though some wore Greek-style sandals to "go with the crowd".[34] [35] Plush footwear was a mark of wealth or status, but being completely unshod need not be a mark of poverty. Cato the younger showed his impeccable Republican morality by going publicly barefoot; many images of the Roman gods, and later, statues of the semi-divine Augustus, were unshod.[36] [37]

Fashions in footwear reflected changes in social conditions. For example, during the unstable centre Imperial era, the military was overtly favoured as the truthful basis for power; at around this time, a tough, heavy, so-called "Gallic sandal" – up to 4 inches broad at the toe – developed every bit outdoor wear for men and boys, reminiscent of the military boot. Meanwhile, outdoor footwear for women, immature girls and children remained elegantly pointed at the toe.[32]

Military costume

For the most part, common soldiers seem to have dressed in belted, knee-length tunics for work or leisure. In the northern provinces, the traditionally brusk sleeved tunic might be replaced past a warmer, long-sleeved version. Soldiers on active duty wore brusque trousers under a armed services kilt, sometimes with a leather jerkin or felt padding to cushion their armour, and a triangular scarf tucked in at the neck.[4] For added protection from wind and weather, they could habiliment the sagum, a heavy-duty cloak also worn by civilians. Co-ordinate to Roman tradition, soldiers had once worn togas to war, hitching them up with what was known every bit a "Gabine cinch"; simply by the mid-Republican era, this was just used for sacrificial rites and a formal declaration of war.[38] Thereafter, citizen-soldiers wore togas only for formal occasions. Cicero's "sagum-wearing" soldiers versus "toga-wearing" civilians are rhetorical and literary trope, referring to a wished-for transition from war machine might to peaceful, civil authority.[39] [40] When on duty in the metropolis, the Praetorian guard concealed their weapons below their white "civilian" togas.[41]

The sagum distinguished common soldiers from the highest ranking commanders, who wore a larger, purple-red cloak, the paludamentum.[42] The colour of the ranker'south sagum is uncertain.[43] Roman armed forces clothing was probably less uniform and more adaptive to local conditions and supplies than is suggested by its idealised depictions in gimmicky literature, statuary and monuments.[44] Nevertheless, Rome's levies abroad were supposed to represent Rome in her purest form; provincials were supposed to adopt Roman ways, not vice versa. Even when foreign garments – such as full-length trousers – proved more than practical than standard issue, soldiers and commanders who used them were viewed with disdain and alarm by their more conservative compatriots, for undermining Rome'southward war machine virtus past "going native".[45] [46] This did not prevent their adoption. In the late third century the distinctive Pannonian "pill-box" hat became firstly a popular, and then a standard item of legionary fatigues.[47]

In Mediterranean climates, soldiers typically wore hobnailed "open boots" (caligae). In colder and wetter climates, an enclosing "shoeboot" was preferred.[48] Some of the Vindolanda tablets mention the despatch of clothing – including cloaks, socks, and warm underwear – past families to their relatives, serving at Brittania's northern borderland.[49]

During the early and eye Republican era, conscripted soldiers and their officers were expected to provide or pay for all their personal equipment. From the belatedly republic onwards, they were salaried professionals, and bought their own habiliment from legionary stores, quartermasters or noncombatant contractors. War machine needs were prioritised. Vesture was expensive to commencement with, and the military demand was high; this inevitably pushed up prices, and a common soldier'south clothing expenses could be more than than a third of his annual pay. In the rampant inflation of the later Imperial era, as currency and salaries were devalued, deductions from military salaries for article of clothing and other staples were replaced by payments in kind, leaving mutual soldiers cash-poor, but adequately clothed.[l]

Religious offices and ceremonies

Most priesthoods were reserved to loftier status, male Roman citizens, usually magistrates or ex-magistrates. Near traditional religious rites required that the priest wore a toga praetexta, in a manner described as capite velato (head covered [by a fold of the toga]) when performing augury, reciting prayers or supervising at sacrifices.[51] Where a rite prescribed the free use of both arms, the priest could apply the cinctus Gabinus ("Gabine sure-fire") to tie back the toga's inconvenient folds.[52]

Roman statue of a Virgo Vestalis Maxima (Senior Vestal)

The Vestal Virgins tended Rome's sacred fire, in Vesta's temple, and prepared essential sacrificial materials employed by different cults of the Roman state. They were highly respected, and possessed unique rights and privileges; their persons were sacred and inviolate. Their presence was required at various religious and civil rites and ceremonies. Their costume was predominantly white, woolen, and had elements in common with high-status Roman bridal wearing apparel. They wore a white, priestly infula, a white suffibulum (veil) and a white palla, with red ribbons to symbolise their devotion to Vesta's sacred fire, and white ribbons as a marking of their purity.[53]

The Flamen priesthood was dedicated to diverse deities of the Roman state. They wore a close-fitting, rounded cap (Apex) topped with a spike of olive-wood; and the laena, a long, semi-circular "flame-coloured" cloak fastened at the shoulder with a brooch or fibula. Their senior was the Flamen dialis, who was the high priest of Jupiter and was married to the Flamenica dialis. He was non allowed to divorce, leave the city, ride a equus caballus, bear upon iron, or see a corpse. The laena was idea to predate the toga.[54] The twelve Salii ("leaping priests" of Mars) were young patrician men, who processed through the city in a course of war-dance during the festival of Mars, singing the Carmen Saliare. They also wore the apex, only otherwise dressed every bit archaic warriors, in embroidered tunics and breastplates. Each carried a sword, wore a short, red armed forces cloak (paludamentum) and ritually struck a bronze shield, whose aboriginal original was said to have fallen from heaven.[55]

Rome recruited many non-native deities, cults and priesthoods as protectors and allies of the state. Aesculapius, Apollo, Ceres and Proserpina were worshiped using the so-called "Greek rite", which employed Greek priestly wearing apparel, or a Romanised version of information technology. The priest presided in Greek manner, with his head bare or wreathed.[56]

In 204 BC, the Galli priesthood were brought to Rome from Phrygia, to serve the "Trojan" Mother Goddess Cybele and her espoused Attis on behalf of the Roman state. They were legally protected only flamboyantly "un-Roman". They were eunuchs, and told fortunes for money; their public rites were wild, frenzied and bloody, and their priestly garb was "womanly". They wore long, flowing robes of xanthous silk, extravagant jewellery, perfume and make-upwardly, and turbans or exotic versions of the "phrygian" hat over long, bleached hair.[57] [58]

Roman clothing of late antiquity (subsequently 284 AD)

Roman fashions underwent very gradual change from the belatedly Republic to the stop of the Western empire, 600 years later.[59] In part, this reflects the expansion of Rome's empire, and the adoption of provincial fashions perceived equally attractively exotic, or just more practical than traditional forms of clothes. Changes in fashion too reverberate the increasing dominance of a military elite within regime, and a corresponding reduction in the value and condition of traditional civil offices and ranks.

In the later on empire afterward Diocletian's reforms, wearable worn past soldiers and non-military government bureaucrats became highly decorated, with woven or embellished strips, clavi, and round roundels, orbiculi, added to tunics and cloaks. These decorative elements usually comprised geometrical patterns and stylised plant motifs, simply could include homo or beast figures.[60] The use of silk also increased steadily and near courtiers in late antiquity wore elaborate silk robes. Heavy war machine-style belts were worn by bureaucrats as well as soldiers, revealing the general militarization of late Roman government. Trousers — considered barbarous garments worn by Germans and Persians — accomplished only express popularity in the latter days of the empire, and were regarded past conservatives equally a sign of cultural decay.[61]

The toga, traditionally seen as the sign of true Romanitas, had never been popular or applied. Most likely, its official replacement in the Due east by the more comfortable pallium and paenula merely acknowledged its disuse.[62] In early medieval Europe, kings and aristocrats dressed like the belatedly Roman generals they sought to emulate, not like the older toga-clad senatorial tradition.[63]

Fabrics

An elaborately-designed golden fibula (brooch) with the Latin inscription "VTERE FELIX" ("apply [this] with luck"), late 3rd century Advertisement, from the Osztropataka Vandal burying site

Animate being fibres

Wool

Wool was the most ordinarily used fibre in Roman wear. The sheep of Tarentum were renowned for the quality of their wool, although the Romans never ceased trying to optimise the quality of wool through cantankerous-breeding. Miletus in Asia Small-scale and the province of Gallia Belgica were also renowned for the quality of their wool exports, the latter producing a heavy, rough wool suitable for winter.[64] For most garments, white wool was preferred; information technology could then be further bleached, or dyed. Naturally dark wool was used for the toga pulla and piece of work garments subjected to dirt and stains.[65]

In the provinces, private landowners and the State held large tracts of grazing land, where large numbers of sheep were raised and sheared. Their wool was processed and woven in dedicated manufactories. Britannia was noted for its woolen products, which included a kind of duffel coat (the Birrus Brittanicus), fine carpets, and felt linings for army helmets.[66]

Silk

Silk from China was imported in pregnant quantities as early as the tertiary century BC. It was bought in its raw state by Roman traders at the Phoenician ports of Tyre and Beirut, then woven and dyed.[64] Every bit Roman weaving techniques adult, silk yarn was used to brand geometrically or freely figured damask, tabbies and tapestry. Some of these silk fabrics were extremely fine – around fifty threads or more per centimeter. Production of such highly decorative, costly fabrics seems to have been a speciality of weavers in the eastern Roman provinces, where the earliest Roman horizontal looms were developed.[67]

Diverse sumptuary laws and cost controls were passed to limit the purchase and use of silk. In the early Empire the Senate passed legislation forbidding the wearing of silk by men because it was viewed as effeminate[68] but there was also a connotation of immorality or immodesty attached to women who wore the material,[69] as illustrated by Seneca the Elderberry:

"I tin see clothes of silk, if materials that exercise not hide the torso, nor even one'due south decency, can be chosen clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body."

(Declamations Vol. 1)

The Emperor Aurelian is said to have forbidden his wife to buy a pall of Tyrian royal silk. The Historia Augusta claims that the emperor Elagabalus was the first Roman to habiliment garments of pure silk (holoserica) as opposed to the usual silk/cotton blends (subserica); this is presented as further evidence of his notorious decadence.[64] [seventy] Moral dimensions bated, Roman importation and expenditure on silk represented a significant, inflationary drain on Rome's gold and silver coinage, to the benefit of foreign traders and loss to the empire. Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices of 301 Advertising set the toll of one kilo of raw silk at 4,000 gilded coins.[64]

Wild silk, cocoons collected from the wild after the insect had eaten its way out, was besides known;[71] existence of shorter, smaller lengths, its fibres had to exist spun into somewhat thicker yarn than the cultivated variety. A rare luxury textile with a cute gold sheen, known equally sea silk, was fabricated from the long silky filaments or byssus produced by Pinna nobilis, a large Mediterranean clam.[72]

Found fibres

Linen

Pliny the Elder describes the production of linen from flax and hemp. Later harvesting, the found stems were retted to loosen the outer layers and internal fibres, stripped, pounded and so smoothed. Following this, the materials were woven. Flax, like wool, came in diverse speciality grades and qualities. In Pliny's opinion, the whitest (and best) was imported from Spanish Saetabis; at double the price, the strongest and most long-lasting was from Retovium. The whitest and softest was produced in Latium, Falerii and Paelignium. Natural linen was a "greyish brownish" that faded to off-white through repeated laundering and exposure to sunlight. Information technology did not readily absorb the dyes in use at the time, and was generally bleached, or used in its raw, undyed state.[73]

Other plant fibres

Cotton wool from India was imported through the same Eastern Mediterranean ports that supplied Roman traders with silk and spices.[64] Raw cotton wool was sometimes used for padding. Once its seeds were removed, cotton wool could be spun, so woven into a soft, lightweight fabric advisable for summer apply; cotton was more comfy than wool, less plush than silk, and unlike linen, it could be brightly dyed; for this reason, cotton and linen were sometimes interwoven to produce vividly coloured, soft but tough cloth.[74] High quality fabrics were likewise woven from nettle stems; poppy-stem fibre was sometimes interwoven with flax, to produce a sleeky smooth, lightweight and luxuriant cloth. Grooming of such stalk fibres involved similar techniques to those used for linen.[75]

Manufacture

Fix-made habiliment was available for all classes, at a toll; the toll of a new cloak for an ordinary commoner might stand for 3 fifths of their annual subsistence expenses. Clothing was left to heirs and loyal servants in wills, and changed easily every bit part of marriage settlements. High quality clothing could exist hired out to the less-well-off who needed to make a adept impression. Clothing was a target in some street robberies, and in thefts from the public baths;[76] it was re-sold and recycled downward the social scale, until information technology roughshod to rags; even these were useful, and centonarii ("patch-workers") made a living by sewing clothing and other items from recycled fabric patches.[77] Owners of slave-run farms and sheep-flocks were advised that whenever the opportunity arose, female slaves should be fully occupied in the production of homespun woolen fabric; this would likely exist good enough for clothing the amend class of slave or supervisor.[78]

Self-sufficiency in clothing paid off. The carding, combing, spinning and weaving of wool were part of daily housekeeping for most women. Those of middling or depression income could supplement their personal or family income past spinning and selling yarn, or by weaving material for sale. In traditionalist, wealthy households, the family's wool-baskets, spindles and looms were positioned in the semi-public reception area (atrium), where the mater familias and her familia could thus demonstrate their industry and frugality; a largely symbolic and moral action for those of their class, rather than applied necessity.[79] Augustus was particularly proud that his wife and girl had prepare the best possible instance to other Roman women by spinning and weaving his wear.[80] Loftier-caste brides were expected to brand their ain wedding garments, using a traditional vertical loom.[81]

About fabric and wear was produced by professionals whose trades, standards and specialities were protected by guilds; these in turn were recognised and regulated past local regime.[82] Pieces were woven as closely as possible to their intended final shape, with minimal waste, cutting and sewing thereafter. Once a woven piece of fabric was removed from the loom, its loose end-threads were tied off, and left as a decorative fringe, hemmed, or used to add differently coloured "Etruscan style" borders, as in the purple-red border of the toga praetexta, and the vertical coloured stripe of some tunics;[82] a technique known as "tablet weaving".[83] Weaving on an upright, manus-powered loom was a dull process. The earliest bear witness for the transition from vertical to more efficient horizontal, human foot-powered looms comes from Egypt, around 298 AD.[84] Even then, the lack of mechanical aids in spinning made yarn production a major bottleneck in the manufacture of textile.

Colours and dyes

From Rome's earliest days, a wide diversity of colours and coloured fabrics would have been available; in Roman tradition, the first clan of professional person dyers dated back to the days of King Numa. Roman dyers would certainly accept had admission to the same locally produced, usually plant-based dyes every bit their neighbours on the Italian peninsula, producing various shades of carmine, yellow, blue, green, and brown; blacks could be accomplished using iron salts and oak gall. Other dyes, or dyed cloths, could take been obtained past merchandise, or through experimentation. For the very few who could afford information technology, cloth-of-gold (lamé) was almost certainly available, possibly every bit early as the 7th century BC.[85]

Throughout the Regal, Republican and Imperial eras, the fastest, most expensive and sought-after dye was imported Tyrian purple, obtained from the murex. Its hues varied according to processing, the most desirable being a dark "dried-blood" ruby.[86] Purple had long-continuing associations with regality, and with the divine. It was thought to sanctify and protect those who wore it, and was officially reserved for the border of the toga praetexta, and for the solid majestic toga picta. Edicts against its wider, more casual use were not particularly successful; it was also used by wealthy women and, somewhat more disreputably, by some men.[87] [88] Verres is reported every bit wearing a purple pallium at all-night parties, not long earlier his trial, disgrace and exile for abuse. For those who could not afford genuine Tyrian purple, counterfeits were available.[89] The expansion of merchandise networks during the early Regal era brought the dark blueish of Indian indigo to Rome; though desirable and costly in itself, it also served every bit a base for faux Tyrian majestic.[xc]

For cherry-red hues, madder was one of the cheapest dyes available. Saffron yellow was much admired, only plush. It was a deep, bright and peppery xanthous-orange, and was associated with purity and constancy. It was used for the flammeum (significant "flame-coloured"), a veil used past Roman brides and the Flamenica Dialis, who was virgin at marriage and forbidden to divorce.[91]

Specific colours were associated with chariot-racing teams and their supporters. The oldest of these were the Reds and the Whites. During the afterward Imperial era, the Blues and Greens dominated chariot-racing and, upwards to a point, civil and political life in Rome and Constantinople. Although the teams and their supporters had official recognition, their rivalry sometimes spilled into ceremonious violence and riot, both within and across the circus venue.[92]

Leather and hide

The Romans had ii methods of converting animal skins to leather: tanning produced a soft, supple brown leather; tawing in alum and salt produced a soft, pale leather that readily absorbed dyes. Both these processes produced a strong, unpleasant odour, then tanners' and tawers' shops were usually placed well abroad from urban centres. Unprocessed beast hides were supplied direct to tanners by butchers, as a byproduct of meat product; some was turned to rawhide, which made a durable shoe-sole. Landowners and livestock ranchers, many of whom were of the elite class, drew a proportion of profits at each step of the process that turned their animals into leather or hibernate and distributed it through empire-broad merchandise networks. The Roman military machine consumed large quantities of leather; for jerkins, belts, boots, saddles, harness and strap-work, simply mostly for military tents.[93] [94]

Laundering and fulling

The almost universal habit of public bathing ensured that virtually Romans kept their bodies at to the lowest degree visually clean, but clay, spillage, staining and sheer wear of garments were constant hazards to the smart, make clean appearance valued by both the elite and non-elite leisured classes, particularly in an urban setting.[95] Most Romans lived in apartment blocks with no facilities for washing or finishing clothes on whatever merely the smallest calibration. Professional person laundries and fuller's shops (fullonicae, atypical fullonica) were highly malodorous but essential and commonplace features of every city and town. Small fulling enterprises could be found at local market-places; others operated on an industrial scale, and would have required a considerable investment of money and manpower, especially slaves.[96]

Basic laundering and fulling techniques were simple, and labour-intensive. Garments were placed in large tubs containing aged urine, then well trodden past blank-footed workers. They were well-rinsed, manually or mechanically wrung, and spread over wicker frames to dry out. Whites could exist further brightened past bleaching with sulphur fumes. Some colours could exist restored to effulgence by "polishing" or "refinishing" with Cimolian earth (the basic fulling process). Others were less color-fast, and would have required separate laundering. In the best-equipped establishments, garments were farther smoothed under pressure, using screw-presses and stretching frames.[97] Laundering and fulling were punishingly harsh to fabrics, merely were evidently thought to exist worth the effort and cost. The high-quality woolen togas of the senatorial class were intensively laundered to an exceptional, snowy white, using the best and most expensive ingredients. Lower ranking citizens used togas of duller wool, more cheaply laundered; for reasons that remain unclear, the clothing of different status groups might have been laundered separately.[98]

Front of firm, fullonicae were run past enterprising citizens of lower social course, or past freedmen and freedwomen; backside the scenes, their enterprise might be supported discreetly by a rich or elite patron, in return for a share of the profits.[96] The Roman elite seem to have despised the fulling and laundering professions every bit ignoble; though perhaps no more than than they despised all manual trades. The fullers themselves evidently thought theirs a respectable and highly profitable profession, worth celebration and analogy in murals and memorials.[99] Pompeian mural paintings of launderers and fullers at piece of work show garments in a rainbow variety of colours, but not white; fullers seem to have been particularly valued for their ability to launder dyed garments without loss of color, sheen or "brightness", rather than merely whitening, or bleaching.[100] New woolen cloth and clothing may as well have been laundered; the process would accept partially felted and strengthened woolen fabrics, and raised the softer nap.[101]

Meet also

- Clothing in the ancient world

- Biblical clothing

- Byzantine dress

- Clothing in ancient Greece

- Ancient Roman military article of clothing

- Roman jewelry

References

- ^ Heskel, J., p. 134 in Sebesta

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus, 82

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., pp. 71–72 in Sebesta

- ^ a b Goldman, N., pp. 223 and 233 in Sebesta

- ^ Ceccarelli, 50. (2016) p. 33 in Bell, Southward., and Carpino, A. A. (eds) A Companion to the Etruscans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-ane-118-35274-viii

- ^ Edmondson, J. C., p. 25 in Edmondson

- ^ Braund, Susanna, and Osgood, Josiah, eds. (2012) A Companion to Persius and Juvenal, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4051-9965-0

- ^ Braund, Susanna, and Osgood, Josiah eds. (2012) A Companion to Persius and Juvenal, Wiley-Blackwell. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4051-9965-0

- ^ Vout, pp. 205–208

- ^ cf. the description of Roman wearable, including the toga, as "elementary and elegant, practical and comfortable" by Goldman, B., p. 217 in Sebesta

- ^ Edmondson, J. C., p. 96 in Edmondson

- ^ Harlow, Yard.Eastward. 'Dressing to please themselves: habiliment choices for Roman Women' in Harlow, Grand.E. (ed.) Dress and identity (Academy of Birmingham IAA Interdisciplinary Series: Studies in Archaeology, History, Literature and Art two), 2012, Archaeopress, pp. 39

- ^ Sebesta, J. 50., pp. 48–l in Sebesta

- ^ Roman Clothing, Function II. Vroma.org. Retrieved on 2012-07-25.

- ^ Goldman, N., p. 228 in Sebesta

- ^ Sebesta, J. Fifty., pp. 67, 245 in Sebesta: citing Nonius M 541, Servius, In Aeneadem, 2.616, four.137

- ^ Sebesta, J. Fifty., p. 49 in Sebesta

- ^ Edwards, Catharine (1997) "Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome", pp. 81–82 in Roman Sexualities. Princeton University Printing. ISBN 9780691011783

- ^ Vout, pp. 205–208, 215, citing Servius, In Aenidem, ane.281 and Nonius, 14.867L for the sometime wearing of togas by women other than prostitutes and adulteresses. Some modern scholars uncertainty the "togate adulteress" as more than literary and social invective: cf Dixon, J., in Harlow, Yard., and Nosch, K-Fifty., (Editors) Greek and Roman Textiles and Wearing apparel: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, Oxbow Books, 2014, pp. 298–304. Some, on like grounds, doubtfulness both the "togate adulteress" and the "togate meretrix": see Knapp, Robert, Invisible Romans, Contour Books, 2013, pp. 256 – 257, citing Horace, Satires 1.2.63, 82., and Sulpicia (in Tibullus, Elegies, 3.16.3 – 4)

- ^ Vout, p. 216

- ^ Edmondson, J., pp. 31–34 in Edmondson

- ^ Clarke, John R. (1992) The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 BC-Advertizement 250. Ritual, Space and Decoration. University Presses of California, Columbia and Princeton. p. 4. ISBN 9780520084292

- ^ For more than general give-and-take see Wilson, A., and Flohr, K. eds. (2016) Urban Craftsmen and Traders in the Roman World. Oxford University Press. pp. 101–110. ISBN 9780191811104

- ^ Bradley, Keith R. (1988). "Roman Slavery and Roman Constabulary". Historical Reflections. 15 (3): 477–495. JSTOR 23232665.

- ^ Appian Civil Wars, 2.120; Seneca, On Mercy, ane. 24. 1

- ^ Bradley, Keith R. (1987) Slaves and Masters in the Roman Empire: A Study in Social Control. Oxford Academy Printing. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0195206074

- ^ Hersch, Karen Thousand. (2010) The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Pregnant in Antiquity. Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780521124270

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., p. 47 in Sebesta

- ^ Olson, Kelly (2008) Apparel and the Roman Adult female: Self-Presentation and Guild. Routledge. pp. sixteen–20. ISBN 9780415414760

- ^ Olson, Kelly, pp. 143–149 in Edmondson

- ^ Croom, Alexandra (2010). Roman Clothing and Fashion. The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN978-1-84868-977-0.

- ^ a b c Goldman, Northward., pp. 105–113 in Sebesta

- ^ Stone, S., in Edmondson, J. C., p. 27 in Edmondson; encounter too Colours and dyes in this commodity.

- ^ Shumba, L., in Edmondson, J. C., and Keith, A., (Editors), Roman Apparel and the Fabrics of Roman Civilization, Academy of Toronto Printing, 2008, p. 191

- ^ Edmonson, J. C., pp. 45–47 and annotation 75 in Edmondson

- ^ Stone, South., p. 16 in Sebesta

- ^ Stout, A. M., p. 93 in Sebesta: the gods needed no footwear, having "no need to touch the ground"

- ^ Stone, Southward., p. 13 in Sebesta

- ^ Phang, pp. 82–83

- ^ Duggan, John, Making a New Man: Ciceronian Self-Fashioning in the Rhetorical Works, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 61–65, citing Cicero's Advertizement Pisonem (Against Piso).

- ^ Phang, pp. 77–78

- ^ Sebesta, pp. 133, 191

- ^ Its modern recreation as an intense red, or indeed whatsoever shade of red, is based on slender, unreliable literary evidence; encounter Phang, pp. 82–83

- ^ The columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius represent such idealised forms of military wearable and armour.

- ^ Phang, pp. 94–95

- ^ Erdkamp, pp. 237, 541

- ^ Vegetius, On War machine Matters, 1. twenty

- ^ Goldman, N., pp. 122, 125 in Sebesta

- ^ Bowman, Alan K (1994) Life and Messages on the Roman Frontier, British Museum Printing. pp. 45–46, 71–72. ISBN 9780415920247

- ^ Erdkamp, pp. 81, 83, 310–312

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1996) "The Deconstruction of Mommsen on Festus 462/464, or the Hazards of Interpretation", p. 83 in Imperium sine fine: T. Robert S. Broughton and the Roman Commonwealth. Franz Steiner. ISBN 9783515069489

- ^ Scheid, John (2003) An Introduction to Roman Religion. Indiana University Press, p. fourscore. ISBN 9780253216601

- ^ Wildfang, R. 50. (2006) Rome's Vestal Virgins: A Written report of Rome's Vestal Priestesses in the Late Republic and Early Empire, Routledge, p. 54. ISBN 9780415397964

- ^ Goldman, N., pp. 229–230 in Sebesta

- ^ Smith, William; Wayte, William and Marindin, 1000. E. (1890). A Lexicon of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Albemarle Street, London. John Murray.

- ^ Robert Schilling, "Roman Sacrifice", Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 78.

- ^ Bristles, Mary (1994) "The Roman and the Foreign: The Cult of the "Great Female parent" in Imperial Rome", pp. 164–190 in Thomas, Northward., and Humphrey, C., (eds) Shamanism, History and the Country, Anne Arbor, The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472084012

- ^ Vermaseren, Maarten J. (1977) Cybele and Attis: the myth and the cult, translated by A. Chiliad. H. Lemmers, London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 96–97, 115. ISBN 978-0500250549

- ^ Rodgers, p. 490

- ^ Sumner, Graham (2003). Roman Armed forces clothing (2) AD 200 to 400. Osprey Publishing. pp. seven–9. ISBN 1841765597.

- ^ Rodgers, p. 491

- ^ Vout, pp. 212–213

- ^ Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome, Penguin Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0 p. 106

- ^ a b c d due east Gabucci, Ada (2005). Dictionaries of Civilisation: Rome. University of California Press. p. 168.

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., p. 66 in Sebesta

- ^ Wild, J. P. (1967). "Soft-finished Textiles in Roman Britain". The Classical Quarterly. 17 (1): 133–135. doi:x.1017/S0009838800010405. JSTOR 637772.

- ^ Wild, J. P. (1987). "The Roman Horizontal Loom". American Journal of Archaeology. 91 (three): 459–471. doi:10.2307/505366. JSTOR 505366.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (1999) Life Along the Silk Route, Berkeley University of California Printing. p. 21. ISBN 0-520-23214-3.

- ^ "Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire" (PDF). www.saylor.org. p. 1.

- ^ Historia Augusta Vita Heliogabali. p. XXVI.ane.

- ^ Pliny Nat.His XI, 75–77

- ^ "The projection Body of water-silk – Rediscovering an Aboriginal Cloth Cloth." Archaeological Textiles Newsletter, Number 35, Autumn 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., pp. 66, 72 in Sebesta

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., pp. 68–72 in Sebesta

- ^ Stone, S., p. 39, and note ix in Sebesta, citing Pliny the Elder, Natural History, viii.74.195

- ^ Croom, pp. 28-29, citing Tibullus one.2.26; the story of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10.30; and Juvenal, Satires half-dozen.352 for rental of vesture

- ^ Vout, pp. 211, 212.

- ^ The notoriously parsimonious Cato the Elder, in his De Agri Cultura, 57, advises that slaves on farming estates be given a cloak and tunic every two years. Columella gives similar communication, calculation that while homespun would likely be "too skillful" for the everyman class of rustic slave, information technology would non be good enough for their masters; simply cf Augustus' pride in his "homespun" wearing apparel. Sebesta, J. Fifty., p. 70 in Sebesta, citing Columella, 12, praef. 9–10, 12.3.half dozen

- ^ In reality, she was the female person equivalent of the romanticised citizen-farmer: Flower, pp. 153, 195–197

- ^ Flower, pp. 153–154, citing Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 73

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., pp. 55–61 in Sebesta

- ^ a b Goldman, B., p. 221 in Sebesta

- ^ Meyers, Chiliad. E. (2016) p. 331 in Bong, Due south., and Carpino, A. A. (eds) A Companion to the Etruscans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-ane-118-35274-8

- ^ Carroll, D.L. (1985). "Dating the foot-powered loom: the Coptic bear witness". American Journal of Archaeology. 89 (1): 168–73. doi:ten.2307/504781. JSTOR 504781.

- ^ Sebesta, J. L., pp. 62–68 in Sebesta

- ^ Bradley, Mark (2011) Colour and Significant in Aboriginal Rome. Cambridge University Printing. pp. 189, 194–195. ISBN 978-0521291224

- ^ Edmonson, J. C., pp. 28–thirty and note 75 in Edmondson

- ^ Keith, A., in Edmonson, J. C., and Keith, A., (Editors), Roman Wearing apparel and the Fabrics of Roman Culture, Academy of Toronto Press, 2008, p. 200

- ^ Sebesta, J., L., pp. 54–56 in Sebesta

- ^ Sebesta, J. Fifty., pp. 68–69 in Sebesta, citing Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 33.163, 35.43, 35.46, 37.84, and Vitruvius, On compages, 7.nine.8, seven.fourteen; equally indigo was imported every bit "bricks" of dye-powder, Vitruvius believed it a mineral.

- ^ La Follette, L., pp. 54–56 in Sebesta

- ^ Sebesta, J. Fifty., pp. 70–71 in Sebesta

- ^ Goldman, North., pp. 104–106 in Sebesta

- ^ Erdkamp, pp. 316, 327

- ^ Bradley, Mark, "'It all comes out in the launder': Looking harder at the Roman fullonica," Periodical of Roman Archeology, 2002, pp. 21-24.

- ^ a b Flohr, pp. 31–34, 68–72

- ^ Flohr, pp. 57–65, 144–148

- ^ Flower, pp. 168–169

- ^ Flohr, pp. 2, 31–34

- ^ Flohr, p. 61

- ^ Flohr, pp. 31–34

Cited sources

- Croom, Alexandra (2010). Roman Wear and Fashion. The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN978-1-84868-977-0.

- Edmondson, J.C.; Keith, Alison, eds. (2008). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Civilisation. University of Toronto Press. ISBN9780802093196.

- Erdkamp, Paul, ed. (2007). A Companion to the Roman Army. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN978-1444339215.

- Flohr, Miko (2013). The Earth of the Fullo: Piece of work, Economy, and Club in Roman Italy. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199659357.

- Flower, Harriet I. (2004). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-00390-2.

- Phang, Sar Elise (2008). Roman War machine Service: Ideologies of Bailiwick in the Late Republic and Early on Principate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781139468886.

- Rodgers, Nigel (2007). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Lorenz Books. ISBN978-0-7548-1911-0.

- Sebesta, Judith Lynn; Bonfante, Larissa, eds. (1994). The World of Roman Costume: Wisconsin Studies in Classics. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN9780299138509.

- Vout, Caroline (1996). "The Myth of the Toga: Understanding the History of Roman Dress". Greece & Rome. 43 (2): 204–220. doi:x.1093/gr/43.2.204. JSTOR 643096.

0 Response to "Ancient Roman Fashion Male Vs Female"

Post a Comment